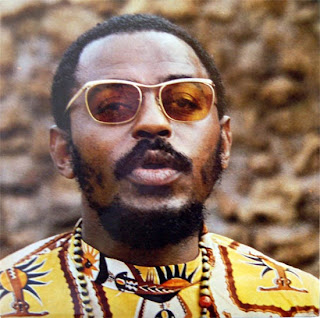

Out of the second wave of free jazz musicians,[1]

Archie Shepp is part of the trinity of tremendously influential and important

saxophonists that shifted the course of the art form, alongside Albert Ayler

and Pharoah Sanders. By the time Shepp travelled to Algiers for the Pan-African

Festival in 1969, all three were calling Impulse! Records home, but they had

sharply diverged in their aims. Ayler was making some ill-advised moves into

jazz/R&B fusion; he would be dead of a presumed suicide a year later.

Sanders was crafting his own spiritualist identity in the post-Coltrane

wilderness and writing some of his best music (including “The Creator Has a

Master Plan”) while he was at it.

Unlike these two contemporaries, Shepp was staying the

course by transforming his sound. On his second Impulse! album Fire Music, with its odes to the

recently assassinated Malcolm X, Shepp had refracted his musical identity directly

through the broader civil rights movement. 1965 was the year of X’s death, the

Watts riot, and riots and racial violence in urban centers around the country.

The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act did not completely end de jure segregation, but they did shift

attention and tension to the de facto segregation

that was the hallmark of Northern urban centers. Anger and fire were the orders

of the day. By 1969, however, Shepp’s philosophy, and in turn his music,

shifted toward cultural nationalism. In 1968 and 1969 he recorded five songs

that would make up his final Impulse! release in 1974. That album was named for

the Los Angeles based US organization’s new black holiday Kwanzaa.

But it is the five albums that Shepp recorded in France and

Algeria for BYG Actuel that represent the culmination of his newfound Pan-African

impulse. Twelve days after his performance at the Pan-African Festival he

embarked on three days of recording,[2]

the first of which spawned Yasmina, a

Black Woman. Yasmina is a

confused record, and it is difficult to reconcile the adventurous, brilliant

first side with the staid, formalist second.

The album’s title track fills the entirety of side one. An eleven

man ensemble, including AACM members Lester Bowie, Roscoe Mitchell, and Malachi

Favors along with Earl Freeman, Clifford Thornton, Arthur Jones, Dave Burrell,

Sunny Murray, Art Taylor, and Laurence Devereaux runs through a twenty minute

percussive ode to an African woman. As with so much of the BYG Actuel catalog,

the piece starts with a Sunny Murray drum solo establishing the bottom-heavy

thrust of the song. He is quickly joined by Favors, Freeman, the other

percussionists, and Shepp on yodeling and other vocals. Favors and Freeman’s

interplay on bass is almost telepathic, and everyone involved seems to tap into

the same headspace immediately, which is unsurprising considering how much

these people all recorded together in such a short period of time. By the time

the horns enter the picture with the main theme of the piece, the

percussion/bass/piano team has already established itself as the dominant force

in the song. For as good as all of the horn soloing is, this group of musicians

completely anchors and dominates the piece. This allows the horns take a break

in the middle of the piece, letting the energy level drop without the piece

losing any momentum.

Shepp in particular has lost none of the fire of his Fire Music days, and Roscoe Mitchell’s

squeaking bass sax provides him with a nice counterpoint. With the amount of

talented players in this ensemble, the twenty minute runtime is filled with

incredible soloing, including a bit of terrific right hand work by Dave

Burrell, so the piece feels much shorter than it is. When the band disappears

and we’re left with just Shepp and a simple accompaniment from Murray, it is

clear that we’ve reached the end of one of the definitive sides of Shepp’s

career.

Side two is a different story. Neither tune is bad; far from

it. They’re just disappointing after “Yasmina, a Black Woman.” “Sonny’s Back,”

written by Grachan Moncur III, finds Shepp working in a quintet with Hank

Mobley, Philly Joe Jones, Dave Burrell, and Malachi Favors.[3]

Mobley and Jones built their careers within the hard bop idiom, and it is a bit

surprising to see them in a group with three free cats. It is even more

surprising that these iconoclasts chose to work within the hard bop form

(albeit with some rough around the edges soloing from Shepp) for a whole album

side. While Shepp and Mobley’s dual soloing near the end of the piece is

enjoyable it all sounds a bit guarded, as if there was some low-level hostility

between the two players (or more likely between their two styles) underpinning

their performances. Moreover, Burrell’s soloing is a bit lackluster, as if he

isn’t really sure what to do with the hard bop leash on. Jones and Mobley not

too surprisingly sound the most comfortable within the piece, and Jones in

particular brings a crispness to the proceedings that isn’t usually present in

Shepp’s sixties body of work. Everyone else give the impression that they’re

trying to prove that they can play more traditionalist material, perhaps to

silence critics who believed that free musicians didn’t really have jazz chops.

The same is true of the melancholy standard “Body and Soul”

that closes the album. Working with the same lineup as “Sonny’s Back” minus

Mobley, “Body and Soul” is full of good but emotionally flat playing. It might

be the most straight-ahead jazz tune in the Actuel catalog, and it’s also

probably the weakest of Shepp’s Actuel period.[4]

He would do much better non-free work on his seventies Impulse! and Freedom

records, when he had followed black nationalism toward funk and Attica. In the

end, side two of Yasmina is required

listening for Shepp acolytes only.

Coming up in the

weeks ahead:

Actuel 05: Gong – Magick

Brother

Actuel 06: Claude Delcloo & Arthur Jones – Africanasia

Actuel 07: Michel Puig – Stigmates

Actuel 08: Burton Greene - Aquariana

Actuel 09: Jimmy Lyons – Other

Afternoons

[1]

I’m defining the second wave as the free jazz explosion that came in the

mid-sixties, after Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman were well established and

Trane had started to explore the sonic cosmos. Second wavers tended to cut

their teeth on Impulse! or ESP-Disk, with a few managing to get records out on

Blue Note or other less traditionally experimental labels (a la Grachan Moncur

III). The third wave consisted of the Chicago and St. Louis cats that showed up

in Paris during the BYG/Actuel period and then migrated to New York at the cusp

of the loft scene.

[2]

Spread out over August 12-16, 1969.

[3]

Considering that he was part of Shepp’s band at the Pan-African Festival and he

was a big part of the BYG Actuel community it’s a bit surprising that he doesn’t

play on this song he wrote or on the album at all.

[4] I

don’t want to give the false impression that I don’t like hard bop, bebop,

swing, or other forms of more straight-ahead jazz. Grant Green’s Idle Moments is one of my favorite jazz

records of all time and I’m on the verge of wearing out my vinyl copy of Duke

Ellington’s 1956 Newport performance. It was just a poor fit for Shepp at the

time.

No comments:

Post a Comment